Small and Tired. The title had me from the get-go. Turns out to be a fascinating 2013 play by Australian Kit Brookman–based loosely on a big and fierce source, the Oresteia. “Loosely” is a key word here. It will not help you to follow the pains and struggles of this contemporary family if you try to directly tie them to the happenings in Aeschylus’ House of Atreus. For the clear lines between action and consequence quiver and blur without the gods and their rules, and this modern family founders in a mess of its own making. Or is it of their own making? Brookman has his Pylades point out, early in his first encounter with Orestes, that even generals are following orders, implying that the gods of war, at least, persist in our time. (Cue the Bob Dylan, 1963. “Masters of War.”)

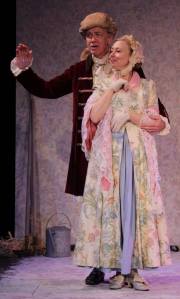

The ensemble in the Common Wealth Endeavors production of SMALL AND TIRED, at Common Ground Theatre through Jan. 23. Photo: Alex Maness.

What the two stories really have in common is war. Long, stupid war, in which men slaughter not just each other but women and children, and their slaughter wounds and kills the women and children they left at home. Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia to pacify the goddess Artemis; in Small and Tired, Iphigenia kills herself after seeing photographs from her (never named) father’s war–bloody Afghanistan. Nobody in the family was right after that. Young Orestes was sent far away to boarding school; now, upon his father’s death (the how of which is never told) he’s come “home” to organize the funeral, since his crazy sister Electra and his puzzling mother Clytemnestra can’t seem to manage, even with the help of Electra’s nice husband Jim.

This Common Wealth Endeavors presentation, currently at Common Ground Theatre (through Jan. 23) is the first US production of Small and Tired. Directed by Common Wealth Endeavors’ founder, Gregor McElvogue, it is the latest show in his ongoing effort to introduce us to English language plays from the rest of the English-speaking world. McElvogue, who is British, trained at the London Central School of Speech and Drama, and he has added hugely to the Triangle theatre scene for years, first as an emotionally powerful actor and clear-eyed director and now as the leader of these Common Wealth Endeavors. His directorial senses of timing and tone have resulted in some very fine performances of demanding plays.

Those senses seemed slightly out of kilter in the Jan. 9 performance that I saw. Although various scenes came vibrantly to life, in others, the actors’ delivery was wooden, their words sounding recited, rather than spoken. By rights, I should have been wrung out by the play’s end, but the erratic intensity levels precluded that. And generally, the pace was a bit languid–it did not contrast enough with the slow-moving scene changes, which in themselves were interesting–dim, cooly-lit, they allowed for tableaux as well as for moving the furniture, and were a marvelous way to indicate the passage of time.

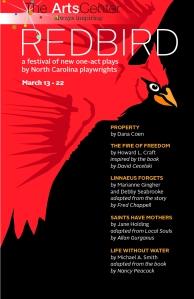

Jane Holding as Clytemnestra, and Justin Brent Johnson as her son Orestes, shortly before their final parting in SMALL AND TIRED. Photo: Alex Maness.

Although all of the men–Justin Brent Johnson as Orestes; Justin Peoples as Pylades; and Lihn Schladweiler as Jim–had some powerful speeches, the woman were more consistent. Laurel Ullman was pretty scary as Electra, but her force could have been greater with a few beats more of silence–she seemed a bit rushed. Jane Holding as Clytemnestra, however, cannot be rushed. Holding spun out her pauses; her unexpected comments burst forth as if from an opened pressure valve. Using stillness and slight shadings of voice and facial expression she communicated implacable will and vast suffering. She knows her line is ending. Iphigenia dead all these years; Orestes gay; Electra childless. All that is left is the long dwindling. Holding distills all that into the poignant moment when she says goodbye to Orestes. That moment, along with many others studded throughout the play’s 100 minutes, make the production’s shortcomings easily dismissible.

For tickets go here .